Bitcoin? A crypto currency represented by a cartoon dog, known as dogecoin? A non-fungible token (NFT) featuring a LeBron James dunk against the Houston Rockets in 2021 selling for over $387,000?1 What are these assets, and what happens if a borrower wants your bank to accept them as collateral for a loan?

Cryptocurrency and NFTs are well-recognized types of electronically created assets, known as digital assets. The driving force behind digital assets is the idea that “centralized” governance creates security risks because a single entity — for example, a bank — administers and controls the so-called ledger (paper or electronic database) for the assets held by the entity. In contrast, digital assets are “decentralized” and created through a peer-to-peer network of computers, commonly known as a distributed ledger, that tracks and records electronic transfers to validate who owns or has the power to buy, sell or otherwise transfer the digital asset. Blockchain is a well-known example of a distributed ledger system stored across a number of digital networks.2 The IRS defines a digital asset as “any digital representation of value which is recorded on a cryptographically secured digital ledger or any similar technology.”3 Of particular importance is the concept that there is no physical asset; rather, there is only an electronic “record” that serves as evidence of the asset.

Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) Article 12,4 which was adopted by the Nebraska legislature in 2021 and became effective on July 1, 2022 (Article 12), establishes the rules for perfecting security interest in so-called controllable electronic records (or CERs, for short), which are electronic records evidencing ownership of a digital asset created with underlying technology that allows the record to be subject to control by a third party.

Under Article 12, control of a CER exists if:

(A) the CER or the underlying technology system in which it is recorded (i.e., blockchain or other distributed ledger), gives the secured party:

- (i) the power to derive substantially all the benefit from the controllable electronic record,

- (ii) the exclusive power to prevent others from deriving substantially all the benefit from the controllable electronic record,

- (iii) the exclusive power to transfer control of the controllable electronic record to another person or cause another person to obtain control of a controllable electronic record that derives from the controllable electronic record, and

(B) “the controllable electronic record, a record attached to or logically associated with the controllable electronic record, or the system in which the controllable electronic record is recorded, if any, enables the person to readily identify itself as having the powers” specified above.5

If the Article 12 definition of what constitutes control of a CER seems vague and abstract to you, you are not alone. The technology that forms the basis of creating and validating digital assets is constantly emerging; therefore, the statute is intentionally drafted “technology neutral” language that would work to establish control over CERs created with existing distributed ledger technology as well as over CERs created with future technology.

Based on the framework for existing distributed ledger technology, control can be obtained by the creation of a multi-signature arrangement that holds the CER. A multi-signature arrangement is a code-based contractual relationship that establishes the authorized signatories (who each hold a distinct cryptographic private key6) and how many of those signatories (or distinct cryptographic private keys) are required to authorize a transfer or other disposition of the CER representing the digital asset.

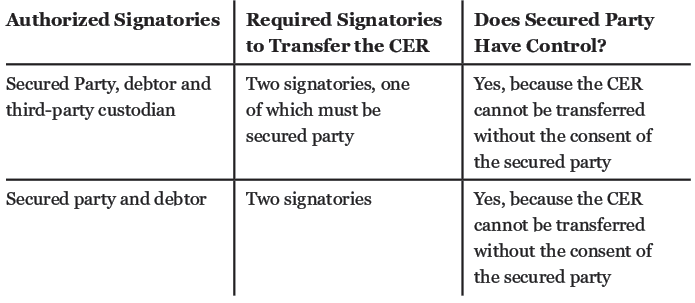

Although the word exclusive is used for purposes of acquiring control of a CER, the power can still be exclusive even if the secured party has agreed to share the power with another person. For example:

If, however, the multi-signature arrangement is among the secured party, debtor and third-party custodian and allows any one of authorized signatories to act, the secured party does not have control because the debtor can transfer the CER without the consent of the secured party.

While the method of obtaining control of a CER may not read the same as a traditional method of control under the UCC (i.e., a written control agreement), the underlying purpose is the same — to enable the secured party to exclude the debtor or other third parties from disposing of the CER without the secured party’s consent.

Please note that, in July 2022, an updated version of Article 12 (Updated Article 12) prepared by the drafting committee was approved by the Uniform Law Commission and American Law Institute and several states. Updated Article 12 maintains the same concept of control of a CER described in this article but is more expansive and provides greater guidance on transactions utilizing CERs. In Nebraska, LB94 was introduced in January 2023 to adopt Updated Article 12. LB94 progressed through several steps of the legislative process, but due to unforeseen legislative delays, did not pass in the 2023 legislative session.

- Ben Stinar, LeBron James NBA Top Shot Sells for Over $387,000, Sports Illustrated, April 16, 2021, https://www.si.com/nba/pacers/news/lebron-james-nba-top-shot-sells-for-over-387000

- IBM: Blockchain, https://www.ibm.com/topics/blockchain

- IRS: Digital Assets, https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/digital-assets#:~:text=Digital%20assets%20are%20broadly%20defined,Stablecoins

- See Neb. Rev. Stat. U.C.C. § 12-101, et seq.

- Neb. Rev. Stat. U.C.C. § 12-105(a)(1)-(2)

- A private cryptographic key is a numerical code used in cryptography to gain access to your crypto wallet to verify transactions and prove ownership, which should be kept secret, similar to a PIN.

Jacqueline Pueppke represents clients in connection with a broad variety of commercial financing and real estate transactions. She represents national, regional and local lending institutions and borrowers in structuring and documenting transactions for commercial real estate financing, construction financing, asset-based financing and agricultural financing. She also represents clients in the acquisition, sale and leasing of commercial real estate.

Nicholas Buda’s practice focuses on creditors’ rights and commercial litigation, the Uniform Commercial Code, commercial real estate disputes, construction law, and appellate advocacy. He routinely assists lending and financial institutions with working out problematic loans and collecting overdue commercial accounts.

Justin Sheldon focuses his practice on commercial real estate, asset based and agricultural financing transactions. He represents both lenders and borrowers in negotiating and structuring transactions.