Banks are no strangers to fraud, including check, wire and email fraud. Yet, identifying the latest fraudulent scheme and, more importantly, who is liable for the resulting loss can be confusing. This article identifies a few examples of commercial and consumer fraud, what a bank can do to help protect itself against losses and who is responsible for the loss.

Part I — Commercial Fraud

A Bank’s Options for Minimizing Liability for Check Fraud

Commercial check fraud is still a widespread issue that banks routinely encounter. Articles 3 and 4 of the Nebraska Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) govern the procedure for allocating the loss resulting from a counterfeit, forged or altered check among the parties involved in the check processing system.

As a general rule, a bank may only charge its customer’s account when the bank is presented with an item that is properly payable from its customer’s account.1 But what happens if a fictitious check or transaction has been presented for payment?

Usually, the item is not “properly payable” because it has not been “authorized by the customer.” In most cases, the bank that is directed to pay the check is strictly liable for charging its customer’s account for a counterfeit, forged or altered check.2

A depository and/or payor bank who wrongfully accepts for deposit and/or pays an unauthorized check may avoid liability in certain, limited circumstances, where it can show that “(1) its customer, the drawer, was negligent; (2) the drawer’s negligence ‘substantially contributed’ to the alteration and (3) the drawee/payor bank paid the check in ‘good faith.’”3

A bank, however, can take proactive steps to protect itself from strict liability by entering into a carefully crafted deposit account agreement with its customer, including requiring the customer to implement services, such as positive pay or cybersecurity standards such as hardware and software firewalls and VPN encryption, to help identify and protect against fraud.4

The following deposit account language may be effective in helping reduce a bank’s strict liability for paying unauthorized checks or transactions:

You agree that if you fail to implement any of these products or services, or you fail to follow these and other precautions reasonable for your particular circumstances, you will be precluded from asserting any claims against [bank] for paying any unauthorized, altered, counterfeit or other fraudulent item that such product, service, or precaution was designed to detect or deter, and we will not be required to re-credit your account or otherwise have any liability for paying such items.5

Part II – Consumer/Personal Fraud

Business Email Compromise Schemes

Email fraud has continued to proliferate in recent years. Targeted phishing attacks had a single purpose — to take over the account of an executive and use the executive’s account to convince employees, vendors or clients to divert a wire transfer to another bank account. The scam is known in federal law enforcement as the business email compromise (BEC).

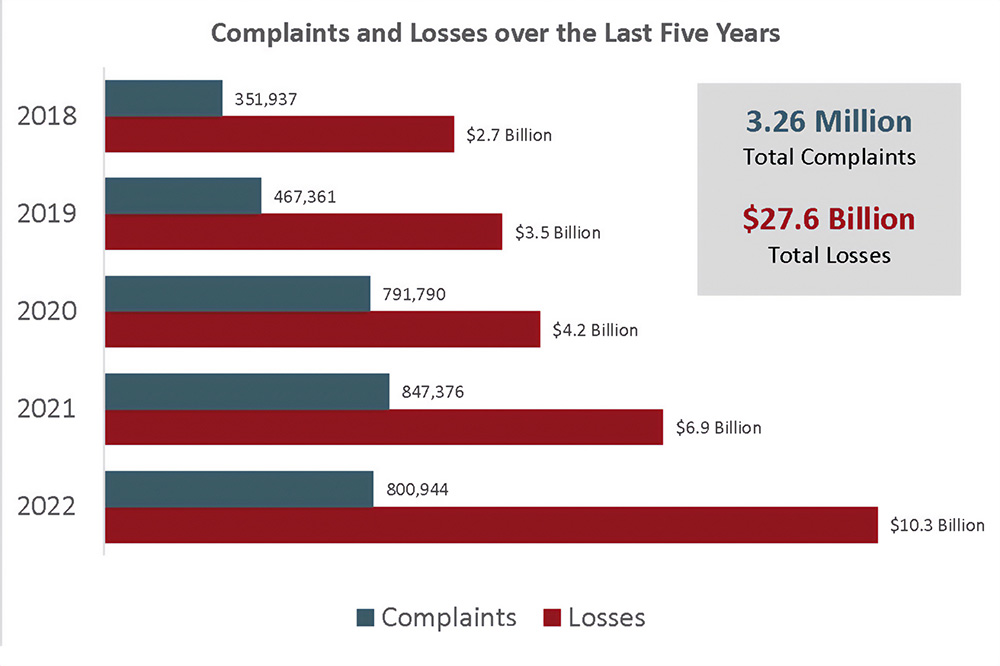

The FBI estimates that over $10 billion was lost to email schemes in 2022.6

Over the last five years, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center has received an average of 652,000 complaints each year. The complaints cover a range of internet scams around the world.

The BEC scams take several different forms, but the most prevalent recently is the supplier or vendor scam. In such a scam, the email of a supplier or vendor is compromised using phished or stolen credentials or credentials found on the dark web. The compromised email account is then used to convince the company that there has been a new bank and new account established to receive transferred funds. The vendor scam is usually discovered only after the legitimate vendor complains that payment has not been received, which could be several months later depending on the terms of purchase, while the customer scam is usually not discovered until payment is not received from the company’s customers.

BEC fraud leaves the two parties with a claim against each other — the payor has usually paid for services or goods rendered, but the payment went to the fraudster, while the payee has provided services or goods but has not received a payment. The question becomes, who is responsible for the loss?

Court Rulings on Diverted Payments

In Arrow Truck Sales Inc. v. Top Quality Truck & Equipment Inc.,7 Arrow paid money for the purchase of 12 trucks. The salesman for Top Quality and the buyer for Arrow negotiated a price of $570,000. Unbeknownst to either, both of their email accounts had been compromised. The fraudster then sent an email to Arrow asking to have the wire payment sent to a different bank account, one controlled by the fraudster. Both parties admitted that the new bank account was different than the bank account in the prior emails. The court, while holding for Top Quality, stated:

“Simply put, [Arrow] should have exercised reasonable care after receiving conflicting emails containing conflicting wire instructions by calling [Top Quality] to confirm or verify the correct wire instructions prior to sending the $570,000. As such, Arrow should suffer the loss associated with the fraud.”8

Although the judge noted that both parties had their email accounts compromised, the court held that neither party was negligent in their manner of maintaining their email accounts. The court then discussed their relative due diligence and duty of ordinary care in terms of the “imposter rule” under the UCC. The imposter rule allows the court to determine liability based on which party is in the best position to prevent the forgery by exercising reasonable care.9

The Arrow case was discussed at length by the court in Beau Townsend Ford Lincoln, Inc., v. Don Hinds Ford, Inc.10 In Townsend, Don Hinds Ford had agreed to purchase approximately $736,225 worth of Ford Explorers. Beau Townsend Ford Lincoln’s email had been hacked, however, and the request for the wire transfer of the money was changed by the hacker to an alternate bank account.

In the Townsend case, the court discussed the issue of fault based on the trial court’s finding for the plaintiff. The trial court stated that “[i]t was not Beau Townsend that instructed Don Hinds to send funds to ‘K.B. KEY LOGISTICS, L.L.C.’ in Missouri City, Texas.”11 However, the appellate court opined that in order to determine who was in the best position to prevent the fraud, the trial court must conduct a trial to determine the facts based on the case and determine to what degree, if any, each party is responsible. The appellate court stated:

“[I]f principles taken from UCC Article 3 are applied, the court would have to determine whether either Beau Townsend’s or Don Hinds’ failure to exercise ordinary care contributed to the hacker’s success, and would then have to apportion the loss according to their comparative fault.”12

A trial on the negligence of both parties as to the loss would allow the court to determine if a company with a hacked email account is primarily at fault or whether the payor who paid the money based on an email without further confirmation or due diligence would be primarily at fault.

A number of other courts have considered the imposter rule in non-BEC-related cases. Based on the reasoning in those cases and the types of issues in BEC cases, the following types of circumstances may be considered by the courts in determining fault:

- The normal course of business for the companies or the industry;

- Prior dealings between the companies (e.g., had the companies only dealt in written checks prior to the incident);

- Whose accounts were hacked;

- Contributory actions (e.g., forwarding a hacked email or deleting an email known to be fraudulent without notifying the other party);

- Common cyber security techniques (e.g., multi-factor authentication);

- Company IT and security policies (e.g., whether the actions were in breach of the company’s own IT and security policies);

- Prior red flags of suspicious activity; and

- Whether a contract or an agreement had actually been reached.

While there is no clear-cut rule for apportioning liability based on current case law, a bank’s business and consumer clients should continue to exercise care and implement proper processes and procedures for initiating and confirming wire transfers to reduce the risk of bearing the liability of a fraud.

- UCC § 4-104(a)

- Travelers Cas. & Sur. Co. of Am. v. Wells Fargo Bank N.A., 374 F.3d 521, 525 (7th Cir. 2004)

- See J. Walter Thompson, U.S.A., Inc. v. First BankAmericano, 518 F.3d 128, 132 (2d Cir. 2008)

- Cincinnati Insurance Company v. Wachovia Bank, N.A., Case No. 08-CV-2734 (PJS/JJG) (D. Minn. Nov. 8, 2010)

- Id. at p. 6 – 7.

- Source is https://www.ic3.gov. If you suspect fraud, notify FinCEN, IC3, and the local FBI or Secret Service office immediately.

- Arrow Truck Sales, Inc. v. Top Quality Truck & Equip., Inc., Case No. 8:14-cv-2052-T-30TGW, 13 (M.D. Fla. Aug. 18, 2015)

- Id. at p. 13

- See, e.g., Nebraska Uniform Commercial Code § 3-404(d), “The drawer is in the best position to avoid the fraud and thus should take the loss.”, comment #3; see also, State Sec. Check Cashing, Inc. v. Am. Gen. Fin. Servs., 972 A.2d 882 (Md. App. 2009).

- Beau Townsend Ford Lincoln, Inc. v. Don Hinds Ford, Inc., Case No. 17-4177 (6th Cir. Nov. 27, 2018)

- Id. at page 18.

- Id. at page 15.